Preface

This post became longer than I expected. It is divided into two main parts: an Introduction with some previously written ideas about what I would like to argue/describe about The Power of the Dog, and then a second part with my notes on watching the film.

Part I

Introduction

Because I have a tendency to over-contextualize, there are two things that I would like to make clear from the outset. First: I am taking as a given that settler colonialism is not a metaphor, is not over, and is an expansive project of both the material and symbolic structuring of the modern world. Second: The land is not a thing, but a relative. As such, any form of cultural expression that does not consider the land as a relative (and act accordingly), but instead figures it as property, is furthering the goals of settler colonialism. In other words, I am starting from the perspective of someone who often cannot watch films for what they say or portray, but rather for what they leave out, what they hide as the latent but omnipresent materiality of the colonial structuring of modernity. For example, I am not concerned with the historical verisimilitude of The Power of the Dog or the class politics of Nomadland, but rather the types of assumptions, claims, and ideologies that they make possible either through their stated aims, or by omission, specifically regarding the land.

I feel this clarification is necessary because I am not a film scholar, and as such I will not be concerning myself with some of the things that film scholars study: things like verisimilitude, aesthetics, memory, form, sound, ideology. I am concerned with the land. And I hope to show why this shift in focus is necessary in what follows.

I have seen both films, but not recently, so I’m going to hazard a hypothesis based on what I remember.

Argument version 1.

Two recent films, The Power of the Dog and Nomadland, position the land as devoid of animacy, which makes possible the project of self discovery (or self-making) that is crucial to both films. While ostensibly framed as a progressive political statement (on queerness in TPoTD and on class and gender in Nomadland), they nevertheless depend on the erasure of Indigenous people and the objectification of the land itself. Land becomes a stage, rather than an ancestor or a relative in these films.

A doubt: This argument seems to be that the films erase Indigenous people. And I want to say, of course they do. Is this surprising? Not really. So perhaps I need to come up with a better argument.

Argument version 2.

Two recent films, The Power of the Dog and Nomadland, erase Indigenous people and appropriate the land in order to produce queerness, in the case of the former, and economic freedom, in the case of the latter. In both cases, the films aim to portray a journey of self-discovery that is predicated on the land as a stage that must necessarily be emptied of Indigenous presence. But they do so in order to demonstrate how a type of individual freedom (erotic, economic) can be achieved by harnessing the power of the land, the land, which cannot be held or cared for by Indigenous people in order for these freedoms to be enacted. Thus, the films argue for the possibility of erotic/white freedom as the result of Indigenous dispossession.

I’m going to watch The Power of the Dog and see what happens.

Part II

I watched it last night, and took some notes. These are my thoughts the next morning.

Blood on wheat.

Leather, straps, saddle, hides,

Hands, dirt, earth, light dim, glowing,

Soundtrack haunting, always discordant.

Queerness is not an identity, but a desire. A yearning. A memory. An instruction in love. But that instruction never happens between them, it is another lesson. Protection, loyalty. Fear.

Masculinity. Its all about men being men, but also the land is the stage for that, the crucial requirement. Men are not men in the city. Men are men on the ranch, doing things that men do on ranches.

Film is divided into sections, 5 parts.

I.

The film opens with a voice in off, “When my father passed, I wanted nothing more than my mother’s happiness. For what kind of man would I be if I did not save her.” A mother who needs saving, and as we will learn, a son who takes on that responsibility. But what is he saving her from? If this is a film about saving, is it not also about salvation? About how men wrestle with their inner demons, what in this case is clearly queerness. It is about how a young man saves his mother, but is it also about how he saves himself from himself? We learn that this is the voice of Peter, Rose’s son.

Peter is tall and thin. Gaunt. Lanky. He is awkward everywhere he goes. But he makes flowers out of paper, newspapers. He loves beauty. But he is also dangerous in a certain way? The scissors, scalpel, the desire to be a surgeon, all of this is about cutting. He cut his father down after he hanged himself. Peter is a man who cuts things.

Takes place in 1925 in Montana. One of the first scenes is of a group of cowboys riding into a town and eating a meal. Phil and George, brothers. There is later a reference to Romulus and Remus. One of them dies. Kills the other. (Right?) I guess we are meant to infer Cain and Able, too.

Phil takes umbrage with the flower, fingers it—fingers its red center like an ass. His dirty fingers rooting around in the center of the flower that Peter had made. Reminds me of the scene in Call Me by Your Name with the peach. Fingering a flower, fingering a peach. A man’s hands in the center of another man’s ass. Flower. Deflower.

This is a metaphor. No, just a visual analogy. We are meant to understand that the flower is part of Peter, and Phil is acting on Peter’s flower, but it is through the tension of Phil’s homophobia that we understand it.

Phil says, “Her boy needed to snap out of it and get human”.

Of course. This is about masculinity and humanness. The cowboys, the men, are human. They are participating in cattle industry. They are occupying the land, they have purchased the land, in order to make money. The house, the upward mobility that George is aiming for by inviting the Governor over to his house to meet his new wife—Rose, who he married unbeknownst to Phil, and this infuriates Phil.

II.

“What is it you see up there, Phil.” Phil is staring at the mountain in the distance, he sees the head of a dog, but the others don’t see it.

This is about seeing what others don’t see. Being seen. Being held by another’s vision. Seeing the dog in the mountain is what Bronco Henry taught Phil—their love? Their erotic past is figured not as physical, but visual. The ability to see—this is reinforced by the later discovery of “Physical Culture” magazine which belonged to Bronco Henry.

Bronco Henry plays this kind of mystical past hero. He is the pinnacle of manhood against which they all measure themselves. But we also understand that he initiated Phil in homoeroticism. They were lovers. They loved each other we assume. Or at least Phil is dedicated to Bronco Henry’s memory in a way that seems only plausible if they were in love. Love does that.

Human. Snap out of it and get human. What a phrase. They are human. Phil is human, even though he is gay? Homoerotically inclined. We know he and Bronco Henry were lovers, but we never see it. (We aren’t allowed to see it, we, viewers, want to be held like Bronco Henry held Phil?)

III.

Phil’s hands on leather, oiling a saddle, going to his secret place. The plaque to Bronco Henry.

George buys Rose a piano, but she is so anxious. He’s invited the Governor over for dinner. We know this will be a disaster. Rose is so nervous. She has no confidence.

There is a Remington statue in the window.

A train billows smoke across a valley. Manifest Destiny.

A snow dusted field.

We learn that Phil was “Phi Beta Kappa and studied Classics at Yale”. Of course. He’s a cowboy who studied Greek. The Greek sin. The Greek vice. This is meant to indicate his queerness. He knows about Pederastia. This is how he was initiated by Bronco Henry. We are meant to understand that this is a type of love between an older man and a younger initiate. This is reinforced by the relationship between Phil and Peter, eventually.

“I stink and I like it”. Smell. Phil doesn’t want to take a bath before the Governor and his wife come over. He doesn’t want to wash the masculinity off of himself.

On the aesthetics: everything glows in this film. The lighting is really clever, really well done. Because of the dim lighting, the candles, the overcast skies, the mood is always a bit charged, a bit dark and menacing. Never a full sunlit day.

Theory: The dim lighting and vision, this is a film about vision. Who can see. Who can be seen. And the test is a shadow on a mountain. But inside, in the interior spaces, there are also shadows cast—across the faces of these characters. We note a correspondence between the face of the mountain and the face of the character. Both are used as a surface upon which a shadow is cast—how do you read those shadows? How do you see upon the face a shape that is meant to signify something. Queerness is a shadow across the face of a man?

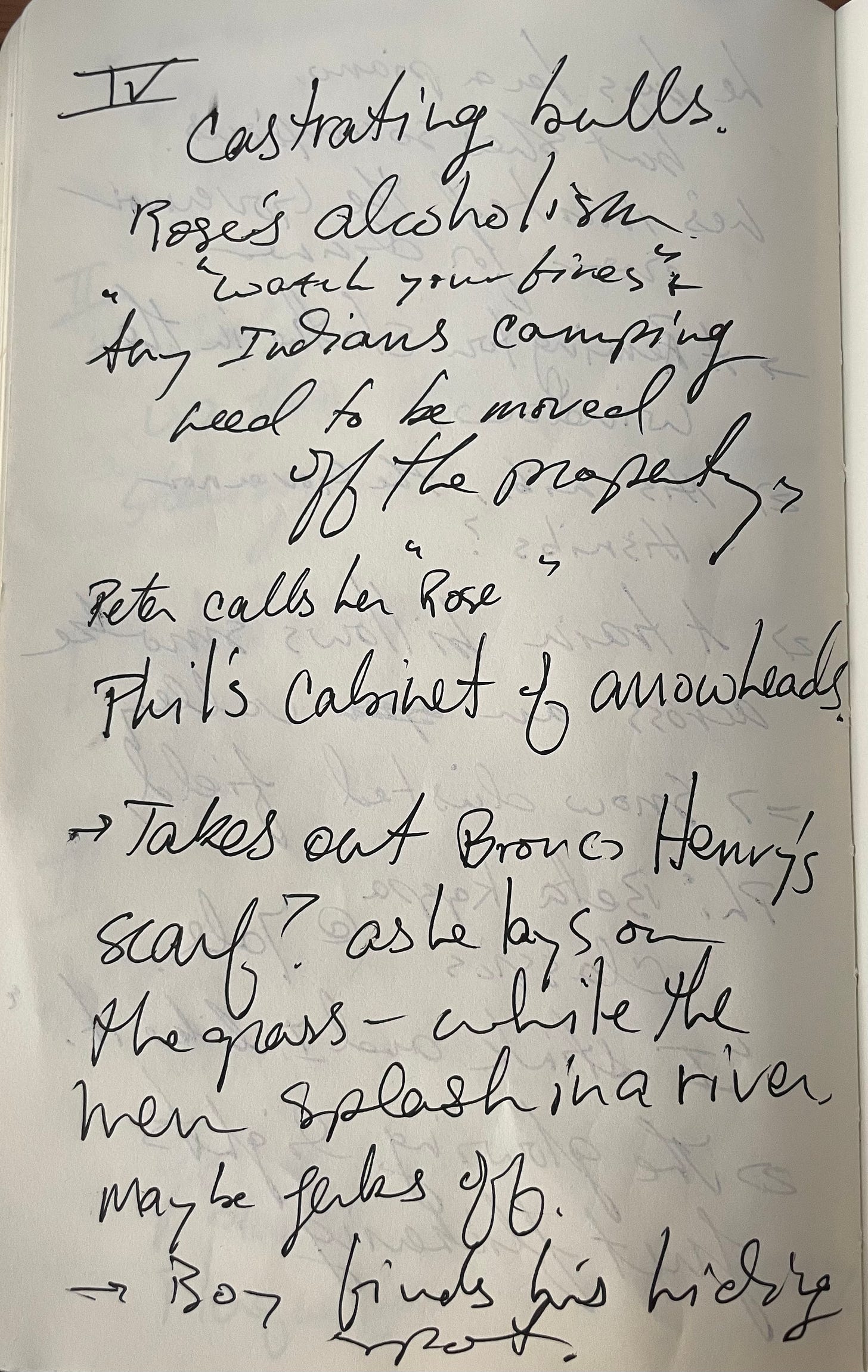

IV.

Opens with a scene of castrating bulls. Phil comes along and doesn’t need gloves to do it. He just squeezes out the testicles.

Rose starts drinking more. Alcoholism as a symptom of her unhappiness?

“Watch your fires and any Indians camping need to be moved off the property”. This is an important quote because it exemplifies the economic structure of the cattle business. They have purchased this land, it is their property. And if Indians are on it, they need to be moved off. “Need to be moved off” in such an impersonal construction.

Phil has a cabinet full of arrowheads.

UFFFF, Phil has been carrying around Bronco Henry’s scarf this whole time? In his pants? And he lays on the grass while the other men splash in a river and caresses himself with it, like he did with BH’s leatherwork, saddle, earlier. He maybe jerks off?

Peter discovers him in that hiding spot, and Phil gets mad and tries to scare him off.

V.

Peter is back from school and hears a pair of crows, goes to look at them.

“Little faggot.” “Little Nancy” the men mutter as he walks in front of them.

But Phil, who had started this whole thing by making fun of Peter’s flowers and his voice, thinks he can get to Rose by taking Peter away from her.

This is the main conflict of the whole film. Phil feels threatened by Rose, because Rose is going to institute a heteronormative household? Which she isn’t good at. And she doesn’t really want to do, I don’t think. She just wants to be saved from where she was. “He’s just another man”. But marrying her was a gesture toward respectability, and away from homosociality. Remember the opening scene where Phil asks George to go away camping with him like they used to. Those days are gone. And Phil is threatened by a woman being in their home.

This is an interesting thing about time in the film. The past is always where men were real men, when things were better, before money or women. LOL.

1805 Lewis and Clark expedition. “Real men back then”.

“Don’t let your mom make a sissy out of you,” Phil says to Peter. As if he is not yet a sissy.

The rope.

Bronco Henry “taught me to use my eyes in ways other people can’t”. We understand this in reference to the shadow dog in the mountain, but also to other men.

This is the thing: the mountain becomes a kind of litmus test, too. Who can see the dog and who can’t. But then, the analogy is to men’s bodies, to homoerotic desire. Who can see another man’s body, eyes, gestures, and understand what others don’t. In this case, Peter is too obvious. He is obviously queer, but Phil is not. He is performing heteronormativity, he is enacting normative masculinity, but he is not that. So the mountain actually becomes an analogy (omg I can’t remember my literary devices, not a synecdoche, what is it?). The mountain becomes a symbol for Phil himself. He is the one who can see it. He is the one who can behold what it hides to others. Just like his body hides things from others, except for Peter, who sees both “it” and the dog in the mountain straight away.

Peter sees the dog in the mountain. He has the eyes for it. He “knows” things.

Blood on wheat. Splinter.

OMG the scene with the Indians. The only time Indians make an appearance in the film. They are silent. They are stoic. They are there to see if they can purchase hides. But they aren’t supposed to be able to. But to get back at Phil, Rose allows them to take some. She implores them. They give her a set of gloves in trade, which she fondles and weeps over.

Some panning shots of the land. 360 sweeping vistas. The shadowy land is menacing. Especially with the music.

Peter’s father hanged himself, with a rope presumably, and now he poisons Phil with a rope (a lasso).

Peter and Phil pass a cigarette between themselves. Wow that is erotic. But Peter knows that Phil has already been poisoned with anthrax, and so this is a kind of death eroticism. A kind of knowing gesture in which Peter finally allows himself to be intimate with Phil, but only once Phil’s death is on the horizon.

Phil dies and Rose and George are going to stay together, final scene Peter smiles knowing he has saved her from Phil.

Final Thoughts

Ok, so, in the end Peter saves Rose from Phil. The film is resolved when one member of the rivalry is eliminated. This means that there are erotic triangles (Sedgwick). But in this case it is not Phil and George (the brothers) fighting over Rose. One is queer, the other is straight. The rivalry is over George—the straight one. Which of them, Phil or Rose, will be able to spend time with George?

Peter is a disruptive figure. His queerness is embodied, plain for all to see.

But the film is not about what is plain. It is about what is hidden. What only reveals itself to those who can see it. To the initiated. And this initiation draws on Greek (Western) epistemologies of erotic arts, of pedagogy.

Teaching to see and teaching to desire are the same in this film.

But this pedagogical praxis is predicated on the elimination of Indigenous people, obviously. We expect that. So what is interesting about this?

Settler colonialism is figured as an ongoing practice of homosocial eroticism, in which the ability to see what others do not is a quality of initiation, a rite of passage, through which a man becomes like the land itself. This is the fucked up part of the film. Phil wants to become the land itself. He wants to be the shadow in the mountain because that is what Bronco Henry taught him to see. He wants to be the mountain. He wants to be what another can see, and he wants to teach Peter to see, too, but Peter already knows how to see. Thus the land is not just the stage for this homoeroticism, but the end goal of its enactment. By learning how to see the body, the land, a settler becomes like the body, the land. And while this is figured as homoerotic, that eroticism is entirely dependent on the elimination of the eroticism of the land itself. The land becomes the body of a man who wants to take that body. Rather than, say, the land is the land, and has its own eroticism.

How can I put this? The film stages the desires of men to be with other men, but also, the desires of men to become (like) the land, and in so doing, learn how to see themselves as part of a landscape, as part of an ongoing historical trajectory from the Greeks to today, through which homoerotic desire (now in the Americas) requires the land for its enactment, for it to even be possible.

Postscript: I would be happy to hear if any of these ideas make sense to you, dear reader. Also, next Friday I will be writing about Nomadland. So if you want to follow along, please do.